You are reading this because you, or someone close to you, is learning Python for scientific programming. This post intends to be a launchpad, providing introductions to the main concepts involved, some guidance on the Python in general, on the libraries most commonly used for scientific Python, and on the best tools to use going into 2026.

It also spends some time on improving your developer experience, especially in the terminal: these choices are quite personal and based on individual preference, so it doesn't impose a particular set of tools, but rather strives to make you aware of what is possible, and inspires you to take ownership of your programming environment instead of accepting the (generally very mediocre) defaults.

It assumes you are starting with no knowledge of Python or its ecosystem, or of general software development.

0. What is Python, and Why?

Python is a very popular programming language that is used all over the world and in almost all branches of software development, especially in data science and scientific programming. It is also one of the easiest programming languages to learn, and is often used to teach introductory classes.

0.1 Okay, but why is it named after a snake?

The Python programming language is named after the British comedy troupe Monty Python, for no reason other than that the creators of the language thought it would be funny. Many programming languages have strange names with no particular connection to their specific properties (contrast FORTRAN, short for FORmula TRANslator, which is an extremely descriptive name for a programming language, to the Java programming language, which has nothing at all to do with coffee beans or Indonesian islands).

1. Python basics

1.0 Getting started with Python

Chances are good that you already have a recent version of Python installed on your computer. Many operating systems, like MacOS, Linux, and Windows often come with Python pre-installed because of how common the language is. If you don't, you can install it for free from python.org.

First, open the terminal: if you're not familiar with it, you should be able to search for an application called 'Terminal', which should open a black box you can type into. Right now it probably looks very unappealing, but we'll fix that up soon!

Type python -V, and press Enter. You should see a response like Python 3.14.0, though the exact version will vary. The newest version of Python is 3.14, released October 2025, with a new version released each fall. The differences between versions are generally quite small, and so long as you have a version from 3.11 onward, you should be fine.

Now try running python by itself, and you should see a change in your terminal: your prompt line should start with a new symbol, like >>>.

You are now in Python's Interactive Shell, also called the REPL (Read-Eval-Print-Loop). You can always exit it by writing exit() and pressing Enter.

There are lots of different ways to write and use Python, and most of your time will be spent writing Python scripts, notebooks, and libraries: but the interactive shell is always just one command away, for when you need to try something really quick.

Try writing print("Hello, world") and entering it. You should see "Hello, world".

If this all works, congratulations! You've written your first, very simple program in Python.

1.1 Basic Python Syntax and Structures

Now that we've confirmed that Python is installed and working on your computer, let's look a bit more closely at the syntax and how to write programs with it.

This is going to be an extremely brief overview: for concrete examples and explanations, check out sections 3 and 4 of the official Python tutorial.

Python code is run line by line. For example, you can use Python as a calculator:

>>> 2 + 2 4 >>> 3 - 2 1 >>> 3 * 8 24 >>> 10 / 4 2.5

And you can also save the values of calculations to variables, as in algebra.

>>> # by using the hash symbol, we can write comments that Python won't run >>> # this is useful for leaving explanations and notes about code! >>> a = 3 >>> b = 4.5 >>> x = a * b >>> x 13.5

We can also define text (which Python calls 'strings' or 'str' for short), and manipulate it, such as by adding text together and printing it.

>>> message = "This is a message for " >>> # add your name here! >>> my_name = "Nico" >>> print(message + my_name)

This is a message for Nico

Strings and numbers (of which there are more than one kind, but we'll get to that later) are two of the three fundamental data types in Python. The third are 'booleans' (named after the British logician George Bool), which are just the True and False values.

Booleans can be created using comparison operators like ==, <, >, and != (equals, less than, greater than, and not equals).

>>> a = 3 >>> b = 4 >>> b < a False

They can be evaluated using the if and else operators, which are very useful for the 'control flow' of a program.

>>> a = 3 >>> b = 4 >>> if a < b: >>> print("a is less than b") >>> else: >>> print("a is not less than b")

Note that above, we ended our if and else statements with colons, and the following lines were indented: in Python, unlike most programming languages, whitespace is significant. If you omitted the indentations above, the program would crash.

You can also organize Python objects into groups: the most common, built-in groups are lists, dictionaries, and sets.

Lists are just what they sound like: sequential lists of objects of various kinds. You can create them by putting a bunch of objects between square brackets, like so, and access elements by index like so:

>>> my_list = ["Cat", 129, "Dog"] >>> my_list ['Cat', 129, 'Dog'] >>> my_list[0] 'Cat'

(Note that the first element of a list is element zero, and the last is element n-1 for a list of length n. This is called 'zero-indexing', and the vast majority of programming languages use this convention.)

Since they're ordered, we can also iterate through them with the ever-useful for/in keywords, and do something for each element!

>>> my_list = ["Cat", 129, "Dog"] >>> for element in my_list: >>> print(element) Cat 129 Dog

Dictionaries define relationships between some key and value. You can create them by putting pairs of objects (each item separated by colons) between curly braces, like so, and access a value using its key, like so:

>>> my_dict = {1: "Dog", 2: "Cat", 3: 129} >>> my_dict {1: 'Dog', 2: 'Cat', 3: 129} >>> my_dict[2] 'Cat'

Finally, sets are unordered collections of unique objects: you can create them using raw curly braces, and they're most often used to check if a certain object exists in the collection or not:

>>> my_set = {'Cat', 'Dog', 129} >>> 'Dog' in my_set True >>> 'Beaver' in my_set False

And of course, all of these features can be combined:

>>> my_list = ['Cat', 129, 'Dog'] >>> for element in my_list: >>> # here we check the type of the object when running the program >>> # the type() syntax represents a function: we'll cover them in the next section! >>> if type(element) == str: >>> print("There's a", element, "in the list!") >>> else: >>> print("What's a number doing here?")

There's a Cat in the list!

What's a number doing here?

There's a Dog in the list!

1.2 Functions in Python

The features we've explored above are just a small fraction of what Python can do, even without any add-ons. But these are the fundamentals, which we'll be building on as we go.

Even these basics are enough to create simple, but useful programs: but it would be extremely tiresome to write things out by hand more than once. To save us headaches and handaches, we have functions.

You're likely familiar with the mathematical definition of a function: an algorithm that takes certain inputs and returns certain outputs, e.g. y = f(x). The actual algorithm which we name f is arbitrary.

The strict mathematical definition of a function also includes a stipulation about the relationship between x and y, where for y = f(x), if the output is not y, then the input cannot have been x. This latter stipulation is somewhat relaxed for most programming languages, where programmers may invoke random number generation which, if used within a function, violates this stipulation: but outside this or other sources of random behavior, this stipulation holds here too.

Starting here, I'm also going to start dropping the >>> in front of everything.

In Python, we define a function as follows:

# this function takes in one parameter (in programming lingo, parameters # are often called 'arguments') and has a single, deterministic output. # this is equivalent to y = f(x) = 2x def f(x): return 2*x

Usually, we want our functions to be doing something a bit more complex than just multiplying an input by 2: here's on of many function we use in McFACTS:

# here we define the name of the function and its arguments # we also indicate the type of the arguments: # here, both of them are floating point numbers # Python doesn't require you to write the types of # arguments like this, but it's generally nice to have def cubic_y_root_cardano(x: float, y: float): # this text here is used to describe what the function is intended to do # while Python does not force you to write these """ Optimized version of cubic_y_root using an analytic solver. Solves the equation: x*y^3 + 1.5*y - y = 0 """ # handle the edge case where x is zero, becomes 1.5*y - y = 0 if x == 0: return np.array([y / 1.5]) # convert to the standard depressed cubic form y^3 + p*y + q = 0 # by dividing the original equation by the leading coefficient x p = 1.5 / x q = -y / x # calculate the discriminant term to see if there will be one or three real roots delta = (q/2)**2 + (p/3)**3 if delta >= 0: # discriminant positive or 0, one real root, two complex roots sqrt_delta = np.sqrt(delta) # what in the world is np.cbrt? In short, it's a cube-root function # defined in the `numpy` library, which we'll discuss later u = np.cbrt(-q/2 + sqrt_delta) v = np.cbrt(-q/2 - sqrt_delta) roots = np.array([u + v]) else: # discriminant negative, three real roots term1 = 2 * np.sqrt(-p / 3) phi = np.arccos((3 * q) / (p * term1)) y1 = term1 * np.cos(phi / 3) y2 = term1 * np.cos((phi + 2 * np.pi) / 3) y3 = term1 * np.cos((phi + 4 * np.pi) / 3) roots = np.array([y1, y2, y3]) return roots

The math being done here is quite basic; you could do most of it by hand, plus a calculator for the roots and trigonometric functions. But by writing it out like this in a function, we can bundle all this logic together, so that elsewhere in our program, we can just write:

x = ... y = ... roots = cubic_y_root_cardano(x, y)

And be done with it, instead of needing to copy-paste this logic all the time.

The effecive use of functions in Python is a longer topic, but these are the basics.

1.3 Classes in Python

In addition to letting you define functions to collect and abstract over program logic, Python also lets you define classes, which allow you to collect data together into a single unit. For example, we might define a black hole with the following data:

class BlackHole(): # note that there's an additional, special argument `self` here, which we # do not pass in by hand: this represents the class itself, and here we # use it to add the x_coord etc. fields to the class itself. def __init__(self, x, y, z, mass): self.x_coord = x self.y_coord = y self.z_coord = z self.mass = mass

Above we create the name of the black hole class, and then below we define a special function called __init__ to define the creation (lit. initialization) of the class. With the above, we can write:

# the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, # Sagittarius B, its coordinates in 3D space defined # relative to itself as the origin, and its mass in solar masses supermassive_black_hole = BlackHole(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1e6)

These functions defined as part of a class are called methods. Unlike the functions we defined earlier, which can be called anywhere in the program, class methods need to be called in the context of an existing object, with some exceptions: the __init__ function above is distinguished by the double-underscores before and after its name, and are called 'dunder methods'. These are special methods given special treatment by the language.

We might also imagine writing a method like

class BlackHole(): def move(self, x, y, z): self x_coord += x self y_coord += y self z_coord += z

Which might be used as follows:

supermassive_black_hole = BlackHole(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1e6) # we move the supermassive black hole half an AU right and 3 AU down supermassive_black_hole.move(0.5, 0.0, -3.0)

A note on Object-Oriented Programming (OOP)

If you've previously taken programming classes in languages like Python or Java, or you've just read about programming in general, you'll likely have heard of something called 'Object-Oriented Programming', abbreviated 'OOP'. This is a philosophy of programming that became dominant in the 90s and 00s, and was extremely influential. Broadly, OOP programming emphasizes programming in terms of discrete objects that unify data and functionality: like the class we defined above! Some languages, like Java, are so OOP-influenced that they don't let you define functions outside of classes!

One of the most prominent ideas of OOP languages is inheritance: the process of creating sub-classes that inherit the functionality of its parent class, in addition to its own unique functionality. For example:

# here we define a class called SpinningBlackHole, which # is a sub-class of BlackHole. It inherits the methods we # defined for its parent class, __init__() and move(), and also # a new `angular_momentum` function which exists for this subclass, # but not for the parent class class SpinningBlackHole(BlackHole): def spin(self, angular_momentum): self.spin = ... # placeholder

Despite Python supporting this behavior, you likely won't encounter this subclassing very often in Python code, and in many codebases you may not encounter classes at all, or only in a very limited capacity.

This is partly because scientific data processing is a domain where OOP features like inheritance are less useful, and also because there's a growing consensus across the software industry that OOP as a philosophy is on its way out, with modern languages stealing some ideas from it (mainly encapsulation) and leaving the rest behind.

Other broad philosophies of programming include Functional Programming (FP), which promotes an entirely different philosophy and style of programming and language design, and Data-Oriented-Design (DOD), which emphasizes thinking about programs as a series of transformations performed upon data.

I will now leave off the subject, noting that this is an argument that has been raging for longer than I've been alive, and any given programmer will probably have very strong opinions on the foregoing.

2. Setting up your Python Environment - An Opinionated Guide

So far, we've been learning Python by just using the interactive shell: this can be convenient in some ways, but it's also very limiting: we're not saving anything we're writing!

The dominant ways of writing Python are scripts and notebooks. We'll focus on scripts here.

In the course of learning how to do this effectively, we inevitably touch on the topic of modern tooling and developer environments. Now is as good a time as any to learn about these other tools and set them up.

2.1 Code Editors and Integrated Development Environments (IDEs)

In theory, code can be written anywhere: by hand on a napkin, in a raw text file, by laying down redstone in Minecraft (I'm only half kidding). Yet most developers care a great deal about the comfort of this experience, and on the ability to easily use supportive tools: the ability to highlight syntax, integrate with version control systems, linters, language servers, and the ability to customize their experience.

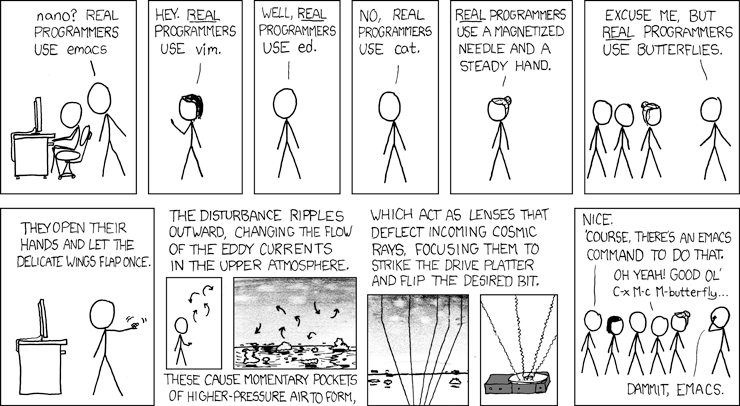

Programmers have been making new code editors and arguing about which one is the best since the dawn of computing: in that time, the only stable lesson is that there is no 'best', and even 'better' is subject to personal taste and needs. For this reason, you are advised against entering and perpetuating the eternal argument about development environments. Live and let live.

Here, I will lay out several common options which you can easily start with, and then propose some less common options that may be worth your attention once you feel like you want to explore new possibilities.

Safe Options:

- VSCode The most commonly used IDE in the world: it's free, somewhat customizable, and there's a ton of user-made addons and extensions for it. Quick to learn, and used in actual industry.

However, it's also not nearly as customizable as other editors, it's bizarrely slow (you won't notice it at first, but on large projects it becomes a pain), and I find that it's unnecessarily cluttered. Acceptable, but not best at anything.

- PyCharm

An editor designed specifically for Python, integrating scripts, notebooks, and with special support for some of the most commonly used packages.

However, because it's designed for one language, it's much less effective for multi-language codebases. The core version is free, with many more features locked behind a paywall.

- Jupyter Notebooks

Not quite an editor in the same was as the others: it's specifically designed for working with notebooks, a specialized interactive Python format that are very commonly used in education and data analysis. You can also edit scripts and other file types using it, but that's not what it's designed for.

Very useful to have available, but it likely won't be your daily driver, especially if you're writing application or library code. Think of it as a more advanced version of the interactive shell.

Adventurous Options:

- Zed

A new editor that's increasingle gaining steam: its design is broadly reminiscent of VSCode, but is broadly cleaner, more customizable, and is focused on speed. If you've been using VSCode for a while and have fel frustrated with its sluggishness, you can migrate over to Zed (even directly importing your custom profile and keybinds) quite quickly and easily. Note that it remains under active development, and there are far fewer add-ons at the moment. See also here

- Neovim

A modern, highly-configurable terminal editor extending Vim. This is my own tool of choice, and I recommend it highly, but not without caveats: to effectively use it, you should get comfortable working directly in the terminal, rather than an application window or browser. You'll need to get familiar with Vim bindings, which take a good deal of practice. Finally, the basic version of Neovim has almost no features, and is meant to be customized by the user. If you put in the time, you'll eventually end up with a hyper-custom environment by and for you, but it takes several months to get to that point. For power users, often the best choice, but requires up-front investment. You can find my current config here.

- Helix

Like Neovim, this is also a modern terminal editor descended from Vim, but it's less customizable in exchange for having a lot more features to start. I generally recommend that people wanting to try Neovim should try Helix first, which starts with around 95% of a nicely tuned Neovim configuration.

- Emacs

Another terminal editor, from a different lineage. I have no experience with it, but many swear by it.

2.2 Effective Use of the Terminal

Even if you prefer to stick to IDEs rather than terminal code editors, familiarity with use of the terminal is a pre-requisite for fluent use of your computer, especially if you ever plan to work with HPC clusters. Not all computing environments have access to graphical interfaces, but they all have terminals.

This section will be written assuming you are using a UNIX system (e.g. Mac, Linux, OpenBSD), rather than Microsoft Windows. Equivalents for all of these exist in Windows as well.

Navigating the Terminal

The key concept for working with your computer from the terminal is the filesystem. Everything on your computer exists as a file somewhere. Every app that you run is a file, every picture you see and sound you hear is a file. The terminal lets you see those files directly and navigate among them.

In the terminal, type ls and press Enter. This will list all the files and directories inside your current directory.

A directory can hold other directories and files. If you keep entering directories, you will eventually either bottom out in a file or an empty directory. It's all just files being organized in different ways.

You can change directories using the cd command. For example, if you see a directory called projects, you can type cd projects and press Enter to move into the projects directory, and then use ls to see that's inside it.

What if you want to move backwards? Use cd ... If you want to move backwards two steps at once, use cd ../.., adding more /.. for each step. You can combine these together to move up and down in the filesystem in a single step, and can also do the same thing with ls to list the contents of other directories without moving into them first.

One final note: your home directory can be accessed from anywhere in the filesystem using the shorthand ~. Just use cd ~ and you'll be right back at the top of your filesystem.

These are the essential basics of navigating in the terminal: other, more effective tools exist, but you will always be able to depend on these.

Moving, Copying, and Removing Files and Directories

There are a few more basic terminal commands you should absolutely be aware of:

move: mv

copy: cp

remove: rm

mv takes an existing file or directory and moves it elsewhere. For example, to move an existing file test.txt to the directory above the current one, we would write mv test.txt ...

cp copies an existing file or directory and places that copy elsewhere, using the same command pattern as mv.

rm removes an existing file or directory. Be careful when using it, especially when deleting directories, as you can end up deleting much more than you had intended. In particular, you could accidentally delete your entire computer if you run certain commands. Don't run rm commands without knowing exactly what they will do, and double checking your current directory before your run them.

2.3 Fortifying and Beautifying your Terminal

Once you start doing a non-trivial amount of work in the terminal, you'll want to customize it and improve your development experience. I include here a few options to explore:

Terminals

While your operating system ships with a default terminal, you can get better ones elsewhere: wezterm, ghostty, kitty, and alacritty are all good options.

Shell Prompts

In addition to the terminal itself, there are several program which change the terminal prompt, generally making it more aesthetically pleasing and informative: Starship and Pure are both popular choices.

Command Replacements

There are even programs which replace basic commands like cd and ls, generally to make them faster or to make their output more aesthetically pleasing. I leave a few here for you to explore:

ZOxide (replaces cd) EZA (replaces ls) bat (replaces cat) ripgrep (replaces grep) dust (replaces du) xplr(replaces fl)

2.4 Dependency and environment management with uv and pip

In addition to writing your own Python code, you'll want to import code libraries written by others. The most common tool used for this is pip. It allows you to import libraries, build projects, and create environments (isolated spaces where you can organize the resources for a project).

However, pip is generally quite slow, and can be a bit hard to use. Nowadays, people are increasinly using a tool called uv, which has the same capabiliies, but is much faster and friendlier.

We encourage you to check out the full documentation for uv, but below we'll present the most common uses you'll have for it, and the equivalents with pip, which you'll see more often in older code.

Creating a new project from scratch:

# no direct equivalent with pip

# with uv

uv init my_project

Creating a new environment for a preexisting project:

cd project_directory

# with venv

python3 -m venv {environment_name}

# with uv

uv venv {environment_name}

source {environment_name}/bin/activate

Note that by default, the environment will be named .venv.

Creating a fresh environment with a different Python version (e.g. 3.12.10, 3.13, etc):

# with venv

venv {environment_name} --python 3.x.x

# with uv

uv venv {environment_name} --python 3.x.x

Installing dependenies manually:

# with pip

pip install {dependency}

# with uv

uv add {dependency}

Or when installing an existing project with a file like requirements.txt or pyproject.toml:

# with pip

pip install .

# with uv

uv sync

2.5 Type checking in Python

There are many differences between programming languages, and one of the most significant is between statically and dynamically typed languages.

Broadly, the difference is that in statically typed languages, the type of each object is known before running the program, while in dynamically typed languages, you generally can't be sure of that without checking while running the program itself.

Dynamic languages can be easier and quicker to learn and produce code, but statically typed languages are generally more stable, and make it a lot easier to predict the behavior of a program before running it the first time.

Python is a dynamically typed language, but many of us have a strong preference for static typing, and want to have those benefits in Python.

This is where type checkers come in: a type checker is a program that runs while you are writing code, and tries to determine statically (that is, without actually running the code) what the type of every single object is.

In languages like Java and Rust, which are completely statically typed, the type checker is a core part ofthe language, and if it fails, that is evidence of a bug in your code.

In dynamically typed languages like Python, however, type checkers do not have the same access to information (or the necessary information doesn't exist) making them much less reliable and much more prone to suprious errors. Despite this, having some type checking is so useful that we put up with the inherent limitations of the type checker.

There are several type checkers for Python, of varying degrees of completeness, thoroughness, and quality. At present, there are two type checkers that are attracting attention: ty, which is created by the same team as uv, and pyrefly, created by Meta.

Both are much more performant than preexisting options, though ty is much faster than pyrefly. Both are also currently in active development, and incomplete. Despite their incompleteness, they are useful enough to work with and rely on.

Personally, I recommend using ty, but this is a matter of personal preference.

3. Scientific Programming Resources in Python

While the Python programming language itself is quite powerful and versatile, and you can create useful programs using the base language alone, most Python codebases in the real world make heavy use of libraries written by others. This is especially true in the sciences, and chances are, you'll write your own libraries for other people to use in the future!

Some of these libraries are domain-specific, such as astropy providing utilities specifically for astronomical calculations. Others, like numpy are more general-purpose, and allow you to more easily do things that are harder, or outright impossible, in native Python. Many of these libraries are not completely written in Python (some have zero native Python at all!), but rather in other languages, like Julia, C, or Rust. For further discussion of this, see section 4.

3.1 NumPy and High-Performance Python

By far the most common library you'll find find used in scientific Python codebases is numpy, abbreviated np. This library is focused on enabling high-performance numeric operations, especially on large collections of data.

In particular, you'll very often see the function np.array(). This requires a short digression into how memory works in computers.

3.1.1 A Long Digression into How Memory Works in Computers

Imagine computer memory as a stretch of land: this land is divided into lots: each lot is big enough to fit multiple objects, like a small house, a bike shed, or a garden, but you can't divide lots into smaller parts.

Now imagine that the lots are arranged in a line. Starting from lot number 1, then number 2, and 3, and so on, far into the horizon. Each lot comes before and after another (expect for the first and last, of course).

Each lot is a byte, which itself contains 8 bits. A bit is the most fundamental unit of computer memory, either a 0 or 1, on or off. It wouldn't be inaccurate to call a bit the quantum of computer memory.

Despite this, however, we tend to talk about memory in terms of bytes, not bits. To use our previous metaphor, a lot can have multiple objects (bits) within it, but those objects don't have their own mailing addresses: only the lot (the byte) has an address.

Formally, we say that a byte is the smallest unit of addressable memory.

Here is an example of a byte, rendered in binary:

00101101

We use bits and bytes to encode information. The byte above, for example, could be used to represent the number 45, or the character -, or many other things, depending on what kind of encoding we use.

Individual bytes can only encode 2^8 = 256 possible values, so we very commonly use more than one byte to represent things: for high-precision decimal numbers, for example, it's common to use 8 bytes, or 64 bits.

Returning to our previous analogy, even though we can't have addressable units smaller than a single lot, and even though a single lot is enough to do something useful (a small cottage and shed, for example), you'll need many lots in order to build something large.

So, we can encode things like numbers in memory. But how do we actually access memory and use it to do things?

Very simply put, a microchip in your computer will request some memory using its address. Your computer then copies the contents of that address in memory into the chip itself, which the chip then reads and uses.

This is simple enough: however, making this work efficiently is much more complicated.

The problem is that modern computer chips can do useful work (mainly a lot of math) extremely quickly: much, much faster than memory can be copied into it. You might have heard of computers having 'clocks' or 'cycles' measured in GHz, such as how most modern computer chips have clock speeds in the range of 4 - 4.5 GHz.

Each tick of the 'clock' is an opportunity for the chip to do some useful work. Extremely simple work, like adding two numbers that are already copied into the chip, takes just 1 clock (about 1/4 of a billionth of a second). Division takes several ticks. Square roots take many more ticks than that.

In order to account for this, modern memory retrieval makes use of caching. To massively oversimplifly, modern computers have multiple layers of memory between the chip itself and main memory (also called RAM, Random Access Memory). These layers are called caches, and contemporary systems will often have three layers of cache: L1, L2, and L3, with L1 being the closest to the chip and thus fastest to reference (at the cost of being very small), while L3 takes considerably longer to access (but not as long as main memory), and is larger.

This caching scheme allows the computer to quickly re-access data it recently accessed. We combine this with the fact that when we request a piece of data in memory, the computer doesn't just grab that data: it grabs the entire 64-byte region it exists in (called a cache line).

This means that if we're accessing lots of small pieces of data (like individual numbers in a sequence), then instead of having to go back to main memory many times, we can just go to main memory once, and then get the rest from L1 cache until we've exhausted that cache line.

To give you a sense of how much of a difference this makes, we can imagine that the clock is like the heartbeat of the computer, and start making some human-scale comparisons: If an L1 cache reference were to take 0.5 seconds (a heartbeat or so), then an L2 cache reference takes 7 seconds, a long yawn.

Going all the way to main memory would take 100 seconds, enough time to brush your teeth thoroughly.

Reading from an SSD would take a weekend. Reading from a disk drive would take a whole university semester.

Sending a packet over the internet from California to the Netherlands and back would take about 5 years.

If you want your program to be performant, you want to ensure that your computer is not doing one minute of work followed by hours or days of waiting for more information.

The most straightforward way to do this, and the first thing you should always try, is to lay out your data in memory in the way that does as much work per memory call as possible. In other words, an array.

An array is simply a sequence of the same kind of data packed as tightly into memory as possible. For example, if we make an array of 64 bit (8-byte) numbers, then every 64-byte cache line will have 8 of those numbers packed into it: this allows us to do one main memory access, followed by 7 L1 cache accesses: much more efficient than if the data was scattered around everywhere!

Unfortunately, native Python does not allow users to create these kinds of arrays. Python's closest equivalent is the list: but lists allow us to have a mix of data of different types and sizes. They do this by containing the address of the data we want, not the data itself: each time you iterate through a list in Python, you're getting the address of the data in memory, retrieving it from goodness-knows where, and then doing the same thing all over again, with no way to ensure that you're avoiding wasted work.

By way of analogy, imagine that you're in Los Angeles, trying to visit the homes of various celebrities: working with an array would be the equivalent of those homes being packed next to each other in the same neighborhood: you just need to drive to the neighborhood and can walk from house to house on foot.

On the other hand, imagine if those houses weren't there: instead, each lot just contained the address, to which you would need to drive through LA traffic just to see one home, and then do it all again.

3.1.2 NumPy Arrays at Last

To reclaim this data structure that Python does not grant us in the core language, we use numpy's implementation. Properly speaking, this data type is called a numpy.ndarray, which is short for 'n-dimensional array', since we can make arrays of arrays.

We can create these ndarrays in many different ways:

import numpy as np # take an existing list and turn it into an array arr = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4,]) # create an array of 0s of a certain length, and then # add new values into it one at a time by index empty_arr = np.zeros(5) for i, val in enumerate([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]): empty_arr[i] = val

Pandas/Polars

Another standard piece of kit for data analysis in Python is pandas, a dataframe library. A full tutorial on Pandas is far outside our scope, but I recommend starting from the official documentation.

In addition to Pandas, another modern alternative is Polars, which is largely similar, but provides several performance-based improvements, stronger typing, and a more functional style.

SciPy

A collection of mathematical algorithms and other convenient tools for general scientific research, built on top of NumPy.

AstroPy

A collection of tools specifically geared towards astronomical research.

4. Using other languages from Python

While any programming language can, in theory, run any program, many programs are much easier to write or run much more quickly when run in some languages compared to others.

For programs which need to be faster than Python will allow, even using NumPy, or which are easier to write in other languages, we can write those programs in another language and then run that other program from Python.

C

How is it possible to run programs written in one language using another? Let's use the example of C.

Originally developed in 1974, C is the oldest programming language still in general use: while contemporaries like FORTRAN and COBOL survive only on the fringes of scientific and commercial software, C is still mainstream after more than 50 years.

This is in no small part because many modern programming languages are themselves written in C, including Python.

What does it mean for a language to be written in another language?

When you write Python code in your editor or in a notebook, that code is just text in a file. In order to run the code, you need to provide that text as input to a computer program. That program is the Python Interpreter, which reads your Python code and 'interprets' it into a series of commands that actually enact your program's behavior.

For example, when you write a function like:

def g(): x=257

The Python interpreter turns it into the following bytecode:

1 RESUME 0

2 LOAD_CONST 0 (257)

STORE_FAST 0 (x)

LOAD_CONST 1 (None)

RETURN_VALUE

At runtime, the bytecode is then used as instructions to run C code. Python objects are also, at the end of the day, represented in C code. For example, this is how a Python integer is represented in C:

struct _longobject { long ob_refcnt; PyTypeObject *ob_type; size_t ob_size; long ob_digit; };

For every integer, we're not only storing the data for the integer itself long ob_digit, we're also storing its reference count (used to avoid having to manually control memory), the number's type, and its current size!

This is another advantage of using numpy arrays over Python's lists: since all elements of an array are the same type and size, we just track those once for the whole array instead of each element in it.

All this just for x = 257! Being simple is very complicated!

Note that the C implementation of Python is not the only one: there are other projects such as mypy that implement Python in Python itself, and IronPython which implements Python in C#. But CPython is by far the most widely used, and the one you're doubtless using.

Since Python is, written in C, and running Python code eventually bottoms out in running C code, does this mean that we can write our own C code and Python just... runs it?

Basically, yes, with a few conditions.

First, calls into C from Python and output from C to Python must follow a calling convention in order to be mutually comprehensible: the requisite types on the C side can be imported with Python.h.

Second, C-side code must respect the GIL - Python's Global Interpreter Lock. Operations involving creating or deleting objects that the Python interpreter needs to track can only be performed when the C code owns the lock.

As of Python 3.14 in 2025, Python allows the user to disable the GIL as an experimental feature, but this is an advanced topic.

A detailed breakdown of writing effective C-Python code is outside of the current scope (if you're part of the McFACTS project reading this, Vera is the local expert on this subject).

Julia

Outside of Python and R, Julia is the language most commonly used in research software: and unlike Python or R, Julia is capable of being quite performant as a matter of course. For that reason, you may sometimes find that you want to call Julia code from Python, either to access a library which does not exist in Python or to improve the speed of your program.

Unlike C-Python, where the C code is compiled ahead of time (AoT) and then executed by Python, Julia is compiled just-in-time (JiT), and running Julia code requires running the Julia compiler alongside it.

This can be done from Python using the juliacall package. Note, however, that introducing juliacall into a codebase can lead to issues further down the line with building and distributing your code to others, as anyone running it must also have a compatible version of Julia installed along with all Python dependencies.

Rust

Rust is a younger systems language which is recently gaining in popularity and adoption, including for speeding up Python code. Rust has very similar performance to C and is compiled ahead of time, but unlike C, it does not require the author of the code to manually handle memory. This, along with modern affordances like a strong type system and sound tooling, are driving a lot of its adoption.

Rust code can be made compatible with Python using the pyo3 crate, and can be compile directly into a Python wheel using the maturin build system.

If you're on the McFACTS project, ask Nico or Vera for more details on this.